Fabrizio del Wrongo writes:

One of the best gifts I received this past Christmas: Metallica guitarist Kirk Hammett’s book covering his extensive horror collection. It’s called “Too Much Horror Business” (after a song by New Jersey punk band The Misfits), and it may be one of the best collectibles books released in recent years. Handsomely bound and filled with color photos, the book is broken up into three sections: one deals with movie posters going back to the ’20s; one with toys, masks, and model kits; and one with original commercial artwork by guys like Frank Frazetta and Basil Gogos. If you know anything about this stuff, you’re already impressed — the posters and Frazetta art alone are worth millions.

I’m one of those people who has the collecting gene. I love seeking out interesting things and then putting them into context. I also love taking in other folks’ collections and listening to their collecting stories. In fact, I think collecting is an activity that is often unjustly ignored by the powers that be, perhaps because the connoisseurship and micro-curating involved in it are at odds with our romantic notions of cultural heroism, which we like to think of as emanating from creative geniuses rather than from, well, people who saved things. But collectors and other nerdy obsessives have had a bigger influence on culture than many people realize.

Some examples which spring to mind:

Henri Langlois

Langlois was the co-founder of the Cinémathèque Française and one of the first people in the world to really care about the preservation of old movies. Without his efforts there may have been no French New Wave or Auteur Theory. Some even think his firing as director of the Cinémathèque helped inspire the mass protests which shook Paris in 1968 — which goes to show just how seriously the French take their movies.

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, AKA The Brothers Grimm

The Grimms’ work collecting and publishing European folk stories had an enormous impact on high and low culture alike. Some things that are just about unimaginable absent the Grimms’ influence: psychoanalysis, modern linguistics, Nazism. Okay, maybe their influence wasn’t wholly positive, but it’s hard to blame them for that.

Charles Darwin

People tend to forget that Darwin’s insights developed out his penchant for collecting things. That’s what a lot of life science consisted of back in the 19th century — collecting, preserving, and comparing specimens. In fact, the sort of “comparative” study that Darwin and the Grimms were engaged in strikes me as being a big part of the intellectual toolkit of the 19th century. Among other things, it led to the development of the modern museum. It even turns up in “Moby Dick”: recall all those passages wherein Melville describes the attributes of various species of whale in almost fanatical detail.

Harry Smith and Alan Lomax

These two guys had a significant impact on the development of popular music after about 1955. Smith was a sort of wackadoodle polymath, and one of his pursuits was collecting old folk records. An anthology covering this collection, called “The Anthology of American Folk Music,” is often cited as a touchstone of pop anthropology. The critic Greil Marcus even wrote a book on the set, claiming that it . . . well, I’m not sure what he claimed because Greil Marcus puts me to sleep. But he said it was really important or something. As for Lomax, he’s famous for collecting field recordings of folk performers. It’s probably no exaggeration to say that without his collecting the work of many of these performers would have escaped preservation — and would never have influenced artists such as like Bob Dylan.

Renaissance and Baroque Humanists

If you know anything about the Renaissance, you know it was inseparable from the collecting activities of various individuals whose possessions and connoisseurship served to inspire the artists who were busy trying to emulate the qualities of antique craftsmanship. Like so many Renaissance developments (one-point perspective, for instance), these collections stressed the importance of the individual. In this case they encouraged the viewer to approach history through the collector’s peculiar (and hopefully very discerning) way of seeing and understanding the world. In later years this trend would develop into the tradition of the curio cabinet, a sort of diorama’d representation of an individual’s tastes and interests which in some ways prefigured the focused exoticism of natural history museums and magazines like “National Geographic.” (I think the curio cabinet, with all its crazy juxtapositions and intertexuality, can also be seen as forerunner of modern sculpture and collage. But perhaps that’s getting a bit too esoteric . . .)

* * *

I don’t mean to compare Hammett’s collecting (or mine) to that of these luminaries. I simply mean to point out that our ideas about what constitutes “culture” are largely dependent on what has been preserved and made comprehensible for us. The world is a jumbled, constantly shifting kaleidoscope of meanings. It’s largely through the lens of individual viewpoints that we’re able to impose some kind of order on it.

But collecting can be a very selfish activity, too. Or perhaps “self-involved” and “inward-looking” are better terms to describe it. Because one of the things it does is allow you to create and sustain your own little world, a Museum of Me and My Interests that isn’t beholden to anything but unique point of view. In extreme cases it can seem like the nesting instinct gone awry — which is the point at which collectors can turn into hoarders. Eventually, the collector-hoarder’s existence within his own little curio cabinet must feel a bit like living inside one of the creations of Jan Svankmajer, the Czech stop-motion animator whose work evokes a world in which the banality of everyday objects has festered into life-threatening menace. Stop motion, it seems to me, is ideally suited for this — it has an ingrown, self-involved quality built right into it. As a viewer you’re constantly aware of the time that has gone into the creation of the illusion. You’re also aware that what you’re watching is the result of a single animator’s intensive and highly-staged interaction with little toys and puppets. Hey, it might be that collecting and stop-motion animating are similar on some level — they’re both efforts to create, sustain, and promulgate a highly personalized bubble of fantasy.

Hammett’s book got me thinking about a lot of this stuff. In particular it got me thinking about the role that fantasy has played in recent cultural history. Of course, Hammett doesn’t directly address any of this, but his book is so good at contextualizing his collection that it serves as a natural springboard for mulling over its anthropological underpinnings.

A fair portion of the tome is devoted to eulogizing the monster kids. Are UR readers familiar with the whole monster kid thing? The term refers to children who grew up in the late ’50s through the early ’70s as aficionados of sci-fi and horror movies, and classic Universal movies in particular. It seems funny to think about today — and it remains little talked about by highbrow cultural historians, who prefer to focus on LSD and rock music — but horror and fantasy were among the most notable cultural things of the 1960s. Spurred on by the late-’50s television syndication of a host of horror classics, as well as by the cheap-o monster and sci-fi movies that proliferated during the Eisenhower years, horror movies crawled back into the popular consciousness just as the Boomers were getting old enough to get paper routes and earn a little pocket-money. And they spent that money not just on movies but on a whole host of monster-inspired products, things like Aurora’s line of model kits, one of the signature toys of the era. A lot of this material is showcased in “Horror Business.” In fact, one of the things the book demonstrates is that the first movie merchandising boom wasn’t built on “Planet of the Apes” or “Star Wars” but on old horror cinema.

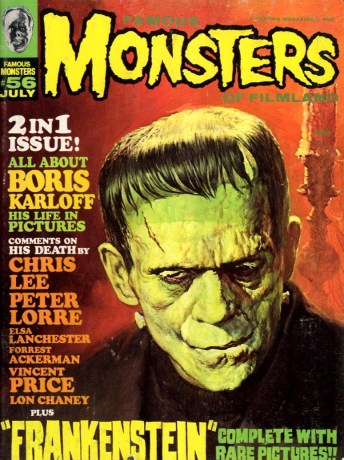

The undisputed flagship of this movement (if an adolescent mania can be called a “movement”) was a magazine known as “Famous Monsters of Filmland.” Published by James Warren and edited by Forrest J Ackerman, “Famous Monsters” emerged right at the end of the ’50s, just as old horror movies were being seen on television and horror-themed comics were on the wane due to industry-mandated content restrictions. Kids ate it up: the first issue was so successful that a second print run had to be ordered to meet demand.

Ackerman — who, it must be noted, was one of the world’s foremost memorabilia collectors — didn’t just write about movies, he wrote about old movies, always taking care to frame them as history and as culture. And he took kids behind the scenes to meet their makers, people like stop-motion animator Ray Harryhausen and golden-age horror director Tod Browning. (In a way, this amounted to a Junior Mints version of the Auteur Theory in that it encouraged a whole generation of young people to take an interest in movie history and behind-the-camera talents.) Ackerman had been around a long time by that point: years earlier, in the ’30s, he’d been instrumental in making science fiction a viable genre, and he’s credited not only with coining the term “sci-fi” but with being the first person ever to wear a nerdy costume to a fan convention. Laugh if you must, but take a minute and think about how big fantasy, fandom, and costuming have become over the last several decades. Here’s a guy who was key to the inception of all of that, the ur-example of the sci-fi/horror/fantasy geek.

* * *

I suppose it’s reasonable to speculate on the sociological implications of the monster kid phenomenon. Why, exactly, did American kids of the ’60s respond to figures like Lugosi and Karloff in ways that were perhaps more intense than those exhibited by their parents back when the Universal movies were first released? Was this sudden identification with the malformed and macabre an adolescent version of the cultural revolution which took hold amongst their older brothers and sisters around the same time? Was wearing a scary mask and drenching yourself in fake blood the kid equivalent of growing your hair long and going out without a bra on? Or was all of this simply an expression of a longing for fantasy that wasn’t being met by the established pop cultural founts of the time?

I won’t pretend to have the answer. But I will note that the monster kid thing roughly coincided with the advent of bunch of other youth culture things, some of which are still with us today: things like “MAD Magazine,” rock-n-roll, and the youth movie. As former monster kid Harold Ramis notes while talking about his 1979 “Animal House,” in the early ’60s there “was a feeling that kids were taking over the country for the first time.” Perhaps, then, the effusive love of horror was simply an expression of the preteen set’s newfound cultural clout. After all, if you give a bunch of little boys a stake in defining the culture, they’re a helluva lot more likely to fixate on the Phantom of the Opera than they are on, well, plain old opera.

As a guy who loves dopey horror movies and other forms of juvenilia, but who also likes to think of his tastes as being just a wee bit on the sophisticated side (I love opera), I confess to having a mixed opinion of all of this. Because I think Landis is right — adolescents did commandeer the culture at some point in the early ’60s, and we’ve been stuck in sticky kidsville ever since. Of course, the Boomer establishment presents this as a triumph: the Official Story is that they swept away the stuffy (and possibly even evil) 1950s and made the world safe for . . . well, I’m not sure. Never-ending adolescence, maybe? That seems like at least one aspect of it. The truth of that was clear by the late ’70s when “Star Wars” was released and instantly became the biggest movie anyone or their uncle had ever seen. The monster kids had their own kids by that point, and the movie hit the culture’s bloodstream like a colossal cross-generational sugar rush. In a sense it was the final victory of Forrest J Ackerman, the eternal kid and professional fantasist. You need look no further than your local multiplex to realize that Ackerman turned out to be a sort of geek Johnny Appleseed. With a comic book movie in every theater, we’re living in a nerd nirvana.

Though he (wisely) doesn’t get into any of this cultural baloney, Hammett, who wrote all of the captions in the book, is great at tying the pieces in his collection into the larger monster kid trend. He’s also good at connecting it to his personal experience. Having grown up in San Francisco while the monster craze was at its peak, he’s uniquely qualified to write about the experience of being pulled in different directions by the popcult trends of the era. (His descriptions of scrounging money for horror paraphernalia while wondering why his older brother wasted his on Jimi Hendrix records are among the book’s most evocative moments.) And he’s uniquely positioned to discuss how, among members of his generation, the love of horror and the macabre eventually merged with rock-n-roll to become heavy metal and punk. While you won’t read much about this in music histories, it’s hard to deny that whatever adolescent urge was behind the ’60s horror fad eventually mutated and re-emerged in the gruesome stylings of bands like Kiss, The Misfits, The Damned, Iron Maiden, and, well, Metallica. As Hammett shrewdly points out, there’s a reason the archetypal metal band, Black Sabbath, took its name from a Mario Bava film.

But the creative venue in which the influence of the monster kids was felt most strongly was the movies. Industrial Light and Magic, the effects house behind George Lucas’ “Star Wars” franchise, took the “Famous Monsters” ethos and made it high-tech. And it’s no coincidence that some of ILM’s principal talents, guys like Phil Tippett and Dennis Muren, had been introduced to the world of visual effects by Ackerman’s writings (they regarded Harryhausen as a patron saint). Other film talents were influenced as well: Landis, Joe Dante, makeup ninja Rick Baker, Sam Raimi, and Peter Jackson have all cited Ackerman and “Famous Monsters” as being essential to their foundations as artists. “When you think of the size of the business,” says Stephen King, “the dollar amount that has sprung up out of fantasy, the people who made everything from ‘Star Wars’ to ‘Jaws,’ well, Forry was a part of their growing up. The first time I met Steven Spielberg, we didn’t talk about movies. We talked about monsters and Forry Ackerman.”

Is it fair to say that a drive to prolong and embellish on the adolescent mindset was one of the defining qualities of that entire generation of movie makers? As many observers have noted, guys like Spielberg and Lucas found their greatest success in updating material that previous generations had regarded as matinée fodder. And the plots of some of the era’s biggest movies were built on the bones of mid-century drive-in classics. “Jaws” is indebted to both “The Creature from the Black Lagoon” and “The Monster that Challenged the World.” Dan O’Bannon’s screenplay for “Alien” borrows heavily from “It! The Terror from Beyond Space,” while its sequel, Jim Cameron’s “Aliens,” cribs bits from “Them!” and “Dinosaurus.” And then there are the more explicit remakes, movies like John Carpenter’s “The Thing” or Philip Kaufman’s great update of “Invasion of the Body Snatchers.” You can forget Rohmer and Bergman and Fellini — this was the signature stuff of that era. And it’s damn hard to ignore its pre-pubescent leanings. Consider this: one of the first things George Lucas did after becoming a bazillionaire was buy his own comic book store. Then he built Skywalker Ranch, a tiny, bubbled-off kingdom devoted to producing colossal reinterpretations of monster kid classics.

By the time the ’90s rolled around the monster kids and their colleagues had come to dominate Hollywood in the same way that former rock-n-roll enthusiasts (or hippies or whatever you want to call them) were starting to dominate politics. Bill Clinton was playing the sax on television at roughly the same time that “Jurassic Park” was wowing audiences in theaters. And like that rather strenuous sax solo “Jurassic Park” was a turning point. When Spielberg needed someone to animate the toothy stars of his upcoming dinosaur flick, he turned to Phil Tippett, Harryhausen’s heir and one of the principal monster kids working in movies. Of course, Tippett planned to utilize the old by-hand techniques, which he’d perfected while working for Lucas. But when former co-worker Dennis Muren screened some newfangled effects for him, Tippett was bowled over. Still working at ILM, Muren had jumped from practical effects into the anything-is-possible world of computers, and his sprightly CGI dinos made Tippet’s stop-motion ones look prehistoric in all the wrong ways. Groking the implications of what he was seeing, Tippett simply turned to Muren and said “it looks I’ve become extinct.”

But in a sense the advent of CGI was the very thing the monster kids had been working towards — it was their apotheosis in the same way that “Star Wars” was the apotheosis of the kind of geek represented by Forrest J Ackerman. Or maybe we can trace it further back and call it the apotheosis of Méliès, because after CGI the outward-looking, Lumiere-derived aspects of film could never again have the same efficacy, the same solidity, the same realness. After all, what is fantasy but the adolescent’s idealized notion of reality? And what is reality if it’s indistinguishable from fantasy? In the end I guess the monster kids succeeded in blowing up the fantasy bubble until it subsumed our very notions of filmed truth — and maybe they gave genuine truth a nudge in the process. CGI is that old inward-looking urge writ large across the face of contemporary culture.

“Too Much Horror Business” can be purchased here.

Related:

- A nice interview promoting the book.

- FEARnet’s review.

- Artist Direct’s review.

- The Misfits song from which the title of Hammett’s book is taken.

- Dennis Muren, Phil Tippett, and Ray Harryhausen.

- Joe Dante’s “Matinee” is a heartfelt valentine to the monster kid era.

- “The Sci-Fi Boys” is a good documentary on that same era. Available to stream on Netflix here.

- The Criterion Collection’s edition of Dennis Muren’s early monster film “Equinox” is a nice primer on the monster kid legacy, as well as on Harryhausen-influenced effects work. (It was also semi-ripped off by Sam Raimi, who used elements of it in “The Evil Dead.”) Includes lots of nice extras. Kudos to Criterion for devoting a DVD to this often overlooked corner of movie history.

- Harryhausen documentary.

- Phil Tippett’s impressively moody animated dinosaur short, “Prehistoric Beast.” Absent CGI, “Jurassic Park” might have looked a lot like this.

- Jan Svankmajer’s “Alice,” available to stream on Netflix here. Also available in its entirety on YouTube here.

- “The New York Times'” obituary for Forrest J Ackerman.

- A video tour of Ackerman’s amazing collection. What a character Ackerman was.

- A very interesting forum thread on Ackerman’s passing.

- A pretty moving collection of thoughts occasioned by Ackerman’s death.

- A fascinating blog post on Heidi Saha, an early costuming star and a friend of Ackerman’s.

- “Monster Kid Online Magazine.”

- Vintage monster toys.

- Vintage Aurora model kits, perhaps the signature monster product of the ’60s and ’70s.

- Nice post on Renaissance and Baroque collecting.

- Harry Smith’s “Anthology of American Folk Music,“ an essential part of any good music collection.

- A good introduction to the field recordings of Alan Lomax.

- Nice piece on Langlois.

- Informative documentary on Langlois, available to rent on Netflix.

Seems like there are two fundamentally opposite types of collectors: the emotional and the compulsive, for lack of better terms. Emotions ultimately guide us toward what we like and away from what we do not, on a gut level, and they all involve a feeling of satiety — you can’t split your sides laughing forever, sob forever, etc. What comes across so strongly among the compulsive types is the utter joylessness of their pursuits, and the fact that they’ll collect anything that fits some criteria — it just goes on and on, with no satisfaction or fulfillment. Those signs point to a broken emotional regulation of behavior.

The emotional — frequently makes use of the items in his collection, gets joy out of each experience, acquires new items by intuition or gut response (like it or hate it), hence happy to get rid of items when he doesn’t like them anymore (and re-acquire them when he gets a hankering again), no self-conscious checklist or project-like goals, does not feel the need to “show off” the collection let alone expect bragging rights. If anything, share it with others and bring them into the joyful experience as well.

I think of someone who collects records or CDs. They don’t just sit there but get listened to, you get lifted up each time you turn them on. You include new ones because you just like them — not to complete a list or out of a self-conscious, “meta” appreciation, like “Hey, think I’ll listen to all of the awfully campy songs in genre X.” You sell and re-acquire the same album according to your fluctuating tastes. You don’t try to impress others with your collection because who cares? If anything, you just want to play the music with the car windows rolled down so that others can join in the fun of hearing “Summer of ’69” when the days start getting longer.

The compulsive — lets a lot of the items sit idle, shows no facial animation or other resonance of the body when using the items, acquires new items by more explicitly articulated check-lists or an anything-goes attitude, gets anxious when he thinks about getting rid of any item, can’t wait to show off the collection and bask in the glory of unlocking the ultimate nerd achievement, and would cringe at sharing his items with others.

I think of video game collectors these days, although the curio cabinet guys from the Renaissance seem to be in the same vein too. They hardly play most of those games, they take on a zombie-like expression and sit perfectly still while playing most of them, they have clear criteria for inclusion — like, I’m going to collect every North American release for the Nintendo including variants, or I’m going to collect every Playstation game that came in a long box. Since the goal is to approach 100% completion of the check-list, any subtraction from their collection gives them anxiety. Ditto for loaning out the games — a temporary backslide away from 100% completion. They all put up “game room tour” videos on YouTube or post pictures with itemized lists on collector nerd websites.

LikeLike

To tie this back into the post, see that comic book on the right in the first picture, with the guy hanging from a noose? No collector actually enjoys that comic. Rather they’ve acquired it because it meets the following criterion for inclusion — was mentioned and pictured in Seduction of the Innocent by Dr. Fredric Wertham, the influential book that launched the anti-horror comic crusade of the mid-1950s.

http://www.lostsoti.org/FoundSOTI.htm

“In general, comic books cited by Dr. Wertham in Seduction of the Innocent are more sought-after by collectors, and are worth more, than comics not mentioned in Seduction of the Innocent. Comic books mentioned in the text of SOTI are worth an average of 20% more than comics not mentioned in SOTI. Comic books PICTURED in SOTI are worth an average of 50% more than comics not mentioned in SOTI!”

So, who cares if they suck? — I’ll get a nanosecond-long buzz from checking off another box.

LikeLike

>>No collector actually enjoys that comic.

Boy, that’s pretty condescending and ungenerous. In a country of over 300 million people, it’s pretty easy for me to imagine that plenty of people “actually enjoy” it.

LikeLike

There’s a really nicely drawn Jack Davis story in that comic. Johnny Craig drew the cover (the best thing about that issue, IMO), but he doesn’t have a story of his own in it, and I’d say he was the best of the EC crime artists. Fantagraphics is putting out an “all-Craig” collection in a few months, which is a much more economical way of enjoying those stories at this point: http://www.amazon.com/Fall-Guy-Murder-Other-Stories/dp/1606996584/

LikeLike

I think the next thing to be collected/curated will be internet videos, or even blogs. Corporations like Google won’t want to archive things forever, and it’ll be up to the nutty collector to archive things like Tonetta videos.

For blogs, the waybackmachine helps but it’s not perfect. Many of the links won’t work, so I could see someone making a project/hobby out of restoring those dead links (what *was* that reference to ucla.edu/~histuffer ??)

LikeLike

Yeah, one of the weirder things about comtemporary culture is that it’s so temporary. A site like 4chan (a major generator of cultural stuff these days) is almost designed to be ephemeral. That’s one of the reasons I love sites like Know Your Meme. They’re doing what they can to save and contextualize things. Still, I don’t have much confidence it’ll be saved in the long run.

LikeLike

Pingback: Elsewhere | Uncouth Reflections

Pingback: I Can’t Even Remember What It Was I Came Here To Get Away From: An Interview With Lloyd Fonvielle | Uncouth Reflections

The architect of the Bradbury building, which SBH and I wrote about here and here, was George Wyman, a draftsman who had no formal training when he designed the building. He later took an architectural correspondence course to bolster his reputation, but none of the buildings he designed subsequently survived.

Why am I posting that information here? Wyman’s grandson was Forrest J Ackerman.

LikeLike

I’m sure Ackerman loved that it was used in “Blade Runner.”

LikeLike

Pingback: “Pacific Rim” | Uncouth Reflections

Pingback: “The Shining”: Stephen King v. Stanley Kubrick v. Conspiracy Theorists | Uncouth Reflections

Pingback: Listing Movies: ’90s Faves | Uncouth Reflections