Blowhard, Esq. writes:

I just finished the first volume of George MacDonald Fraser‘s high-spirited and rollicking The Flashman Papers series. For those new to the books, the series of 19th century historical novels chronicles the exploits of an English army officer and self-described “cowardly scoundrel” as he lies, cheats, and whores his way through the British Empire. I was at a lecture once where James Ellroy said, “Good cops make bad fiction.” Well, consider this book Exhibit A for that proposition. Harry Paget Flashman may be a bully and a cad, but isn’t part of the fun of fiction vicariously living through other people? Feminists are always going on about wanting stories with “strong” female characters, but these novels are hugely entertaining and the only things “strong” about the lead are his instinct for self-preservation and sexual appetite. As soon as he’s in danger, all morality goes right out the window.

Published in 1969, one of the wonderful things about the book is how refreshingly un-PC it is. Here’s Flashy’s post-coital assessment of his future wife, a Scottish lass he seduces while temporarily exiled from London:

Ignorant women I have met, and I knew that Miss Elspeth must rank high among them, but I had not supposed until now that she had no earthly idea of elementary human relations. (Yet there were even married women in my time who did not connect their husbands’ antics in bed with the conception of children.) She simply did not understand what had taken place between us. She liked it, certainly, but she had not thought of anything beyond the act — no notion of consequences, or guilt, or the need for secrecy. In her, ignorance and stupidity formed a perfect shield against the world: this, I suppose, is innocence.

It startled me, I can tell you. I had a vision of her remarking happily, ‘Mama, you’ll never guess what Mr Flashman and I have been doing this evening….’ Not that I minded too much, for when all was said I didn’t care a button for the Morrisons’ opinion, and if they could not look after their daughter it was their own fault. But the less trouble the better: for her own sake I hoped she might keep her mouth shut.

I took her back to the gig and helped her in, and I thought what a beautiful fool she was. Oddly enough, I felt a sudden affection for her in that moment, such as I hadn’t felt for any of my other women — even though some of them had been better tumbles than she. It had nothing to do with rolling her in the grass; looking at the gold hair that had fallen loose on her cheek, and seeing the happy smile in her eyes, I felt a great desire to keep her, not only for bed, but to have her near me. I wanted to watch her face, and the way she pushed her hair into place, and the stead, serene look that she turned on me. Hullo, Flashy, I remember thinking: careful, old son. But it stayed with me, that queer empty feeling inside, and of all the recollections in my life there isn’t one that is clearer than of that warm evening by the Clyde, with Elspeth smiling at me beneath the trees.

But the women aren’t mere pushovers and, without spoiling any of the surprises, each gets her revenge.

Fraser is equally blunt about race as he is with gender. Likely both out of a sense of verisimilitude and crude thrill, his characters freely use the n-word to describe the Indians and Afghanis. There’s enough Orientalist otherness in this book to give a cultural anthropology undergrad a stroke. But, much like the women in the story, the unruly natives frequently give their white oppressors their comeuppance. The primary set-piece of the novel is the British Army’s catastrophic withdrawal from Kabul in 1842 which Fraser portrays in unsentimental and unsparing detail. A force of over 14,000 — consisting of British troops, East India Company regulars, and over 10,000 civilian workers and their families — was slaughtered by the Afghanis as they tried to retreat through snowy passes. (An imperial army defeated by indigenous warlords united by a common enemy? Nah, nothing to learn from that.)

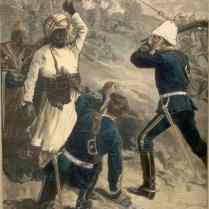

Given that the novel hews closely to real historical events, Fraser occasionally drops in footnotes to primary sources. The character of Mackenzie, one of Flashman’s fellow soldiers, is based on Lieutenant-General Colin Mackenzie, author of Storms and Sunshine of a Soldier’s Life, a book you can download for free at the Internet Archive. Likewise, another of Fraser’s sources, Kaye’s The History of the War in Afghanistan, is also in the public domain. Fraser also references some famous artwork that I was able to track down. Here’s a little gallery I put together that covers both the First and Second Anglo-Afghan Wars. (Notice how the sixth image, The Last Stand of the 44th Regiment, is used in the book cover.)

Click on the images to enlarge.

With so many uncopyrighted, freely-available primary sources available, why don’t more publishers cull the best these to produce enhanced electronic editions of their books? A few years ago I read Devil in the White City, an account of the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. I got frustrated reading the author’s descriptions of Daniel Burnham’s visually marvelous White City while the book itself only featured a dozen or so small images. A few minutes with Google, though, revealed a wealth of high-quality photos, park guides, and other ephemera. Publishers: if you’re determined to make us pay more for ebooks, why not take advantage of the technology and add some value by including curated links to these historical materials? Can you just add some more pictures, please?

Another thing the book got me thinking about is how great the English are at adventure stories. Some examples that spring to mind are H.R. Haggard‘s Allan Quatermain, Conan Doyle‘s Professor Challenger and Brigadier Gerard (and Holmes, of course), C.S. Forester‘s Horatio Hornblower, Patrick O’Brian‘s Aubrey-Maturin, Fleming‘s James Bond, Tolkien‘s Lord of the Rings, Rowling‘s Harry Potter, and Adams‘s Hitchhiker’s Guide. Edgar Rice Burroughs may have been an American, but Tarzan was the son of English aristocrats. These stories and characters, which have been incredibly influential and enduring, almost comprise an alternative 19th and 20th century literary history to the usual progression taught by English profs. Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, that freshman lit mainstay, belongs just as much to the English adventure genre as it does to post-colonial literary fiction. Not to mention the first modern novel is a tale of a knight and his squire and the first English novel is a survival story about a dude shipwrecked on an island.

So what’s your experience with the genre? Which are your favorite adventure stories? Does this stuff have legitimate literary merit or is it just for kids?

Related

- Fraser’s inspiration for Flashman was the antagonist in Thomas Hughes’s Tom Brown’s School Days, a Victorian-era classic published in 1857 that’s unread by me.

- Until I started researching this piece, I had no idea that Malcolm McDowell starred as Flashman in a film directed by Richard Lester from a script by Fraser. Royal Flash was based on another staple of Victorian adventure fiction, Anthony Hope‘s The Prisoner of Zenda. Fraser also wrote the script for the Bond film Octopussy.

- Fraser lived on the Isle of Man “as an exile from the modern world.” Flashman was turned down a dozen times before P.G. Wodehouse’s publisher picked it up. Notice how Wodehouse supplies the blurb for the cover.

- This guy has published two novels of Flashman fan fiction.

- Back here I wrote about Sherlock Holmes.

- Penguin’s Boy’s Own Books, the covers of which are shown above, feature many of the authors I’ve mentioned.

- The Art of Maniless shares its list of 50 essential adventure books.

- I’ve been meaning to get my hands on a copy of The Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction for a while.

- Come to think of it, Lloyd Fonvielle’s Bloodbath sorta reminds me of a 20th-century noir version of Flashman. Fonvielle’s book also supplies globe-trotting adventure and cameos by real-life historical figures all wrapped up in a page-turning story, not to mention Bloodbath is the first in a projected series. You can buy Bloodbath for Kindle here.

Epic posting. I love Fraser too. And I’m completely scandalized that he isn’t considered to be one of the great book-fiction creators of the last half-century.

LikeLike

If the other volumes are half as good as this one (and the reviews seem to indicate they are), yeah, it’s a major accomplishment.

LikeLike

I’ve read four of them and they were all amazing. As entertaining as Wodehouse, as spirited and full of mischief as Westlake, and a fun way to learn some history too.

LikeLike

People will likely be reading this stuff long after they’ve forgotten most of David Foster Wallace’s footnotes.

LikeLike

The reddit nerds would have an apoplectic fit if you ever suggested such a thing.

LikeLike

I wonder when we’ll start reading the first essays/blogpostings where literary youngsters confess that they’ve lost their infatuation with DFW … Soon, I’ll bet.

LikeLike

>>I wonder when we’ll start reading the first essays/blogpostings where literary youngsters confess that they’ve lost their infatuation with DFW … Soon, I’ll bet.

I hang around r/books, and every month or so, someone posts something like, “I’ve been reading Infinite Jest for a while now, I don’t really get it, I’m confused, should I continue?” Then a comment thread ensues during which most everyone enthusiastically encourages the OP to keep plowing head. “It’ll all make sense later,” they say. Here’s a fairly typical example: http://www.reddit.com/r/books/comments/14osw6/infinite_jest_do_i_continue/

The top answer starts out, “A lot of what I loved about IJ was at the micro level: the sentence level. I loved the sentences. You could get like a page-long sentence and have to parse it out like a puzzle. A lot of what kept me reading was this sense of a puzzle to be figured out.”

It’s pretty clear that a lot of the people on that board are high school and college age. For them, the only genres that exist are science fiction, fantasy, and the classics they’ve been assigned in school. I’m guessing after they finish school and start exploring the arts on their own, they’ll find DFW doesn’t resonate with them anymore. But I dunno, we’ll see. An interesting thing to track.

LikeLike

That moment when the typical bright lib-arts ex-college kid discovers, really discovers, that he/she isn’t in school any longer (and that you get to read for pleasure now) is a big one. Usually hits at around age 30, and can really shake a person up.

LikeLike

Check out DFW’s syllabus for the undergrad fiction course he taught: http://flavorwire.com/373519/learn-from-the-best-10-course-syllabi-by-famous-authors

James Ellroy, Larry McMurtry, Thomas Harris, Stephen King, Jackie Collins. He says of his selections, “Don’t let any potential lightweightish-looking qualities of the texts delude you into thinking that this will be a blow-off-type class. These ‘popular’ texts will end up being harder than more conventionally ‘literary’ works to unpack and read critically.”

LikeLike

I recently gave IJ a go and put it down after 1/3 of the way through. It wasn’t horrible, but it wasn’t light reading either. I decided it wasn’t worth the time.

I had read some of DFW’s non-fiction pieces and thought they were very well done, but I found IJ to be stylistically quite different. The prose is quite dense, with a lot of technical jargon and obscure references to anatomy and pharmacology. There’s also digressions into film theory and other areas, which seemed rather pointless. It was hard to get a feel for more than one or two characters, because the innumerable remainder were so thinly sketched out that after a while I gave up trying to figure out who they were.

DFW was obviously a very smart man and a shrewd observer of the modern world, but IJ felt like a communication breakdown. There’s probably something great in there, but it’s in such a mangled and distressed form that I didn’t think it was worth digging for.

LikeLike

Excellent work, dear Mr. Blowhard. The Flashman novels are among the Manolo’s very favorite books.

LikeLike

Hey, thanks The Manolo. Hard to imagine a more entertaining series.

LikeLike

Pingback: Paleo, Brokeness, Wall Street & Winning – Voice of Eden Feb 25 | Koanic Soul

You left out M.E. Palin’s “Ripping Yarns.”

LikeLike

Never heard of that one. Adding it to my list, thanks.

LikeLike

All the Flashman books (I’ve read ’em all more than once) are superb from beginning to end, but for my money the best is “Flashman at the Charge”, which puts him at Balaclava with the Light Brigade. And for all I’ve loved Wodehouse and Fraser for most of my life, I’ve never knew the two names were connected until I read this post. Amazing!

LikeLike

Great posting, Blowhard, Esq. I read the first three Flashman books this summer, along with a couple of Bonds (Casino Royale and Dr No, nos. 1 and 5 in his bibliography). One of the pleasures of historical fiction like Flashman is the taste of the Zeitgeist it gives you. Come to think of it, that was one of the pleasures of Bond, too. The Fleming of Casino Royale had a casual clued-upness about the post-war world that was a pleasure to drink in.

LikeLike

Thanks, CM. Casino Royale has been on my to-read list for a while. Bumping it to the top.

LikeLike

It’s a bit slow. When Fleming wrote it, he knew a lot about spycraft, but not so much about plotting and suspense. Btw, my self-description on Gravatar is lifted directly from Fleming: it’s how he described Bond.

LikeLike

“Quartered Safe Out Here” is Fraser’s memoir of his time as an enlisted man in the British Army in WW2 Burma. Experiences that likely served as foundations for parts of Flashy’s adventures, but poignant reading in its own right.

LikeLike

Thanks for mentioning that book and the fact that Fraser was a soldier himself — I should’ve noted both in my post.

LikeLike

You might also be interested in his diatribe against political correctness at http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-506219/The-testament-Flashmans-creator-How-Britain-destroyed-itself.html

LikeLike

Excellent, thanks.

LikeLike

Love Flashman! – read about 3-4 but currently re-reading the first and was researching the Kabul retreat – thanks for your links I’ve downloaded the first-hand accounts you posted.

LikeLike

Pingback: Art Du Jour | Uncouth Reflections

Pingback: My Year in Books | Uncouth Reflections

Pingback: A Typical Routine Day | Uncouth Reflections

Pingback: The UR Syllabus of Shitlordery | Uncouth Reflections