Sax von Stroheim writes:

Continuing my series of reviews of superhero comic books that I bought out of a combination of (a) their being on sale, (b) a modest amount of curiosity about them, and (c) my own incurable superhero comic book addiction, we come to Gail Simone and Adrian Syaf’s Batgirl. Gail Simone is one of those writers who is always being described as a “fan favorite”, which seems to mean that her Twitter followers (there were 45,551 of them when I checked this morning) outnumber the people who actually buy her comics (36,666 people paid for a copy of the latest issue of Batgirl). I like her writing—it reminds me a lot of the comics I liked best as a teenager—but if I’m being honest, the most interesting thing about her is that she’s one of the few women writers who has consistently written superhero comics for DC. (Even in a subculture known for its “women problem”, DC seems to be a particularly inhospitable place for women).

This Batgirl series (like the Batman comics I reviewed, here, and the Red Hood comics I wrote about, here) is part of the “New 52” initiative, a company wide “reboot” that DC Comics rolled out at the end of 2011. Essentially, DC cancelled all of their superhero titles, and restarted them at issue #1, with brand new storylines and, in some cases, brand new interpretations of the characters. The idea seems to have been to provide a better jumping on point for the hypothetical “new reader” who may have liked one of the contemporary superhero movies, but would have found it a bit intimidating to start reading the 713rd issue of an ongoing comic book series.

(Of course, these new readers don’t really exist, which is a good thing because, as you might be able to guess from my reviews, these comics are completely opaque to anyone who hasn’t already been following them for years. I suspect the real reason DC engaged in the “New 52” project was to cause enough hype to momentarily jack up their market share so they could outsell Marvel’s comics for a month or two.)

The big change that came with Batgirl #1 was that Barbara Gordon became Batgirl again. Now, if your only familiarity with Batgirl is from the terrific 1966 television series starring Adam West and Burt Ward, then Commissioner Gordon’s daughter Barbara is the only Batgirl.

But in the comics, it’s much more complicated than that: Barbara Gordon was Batgirl until Alan Moore’s infamous The Killing Joke. In that story, the Joker, meaning to terrorize Commissioner Gordon, busts into his home and shoots Barbara. She’s paralyzed by the injury and confined to a wheelchair for life. However, she ends up using her spare time to become the greatest computer hacker in the world, and under the codename Oracle, she’s one of Batman’s most valued allies.

For years, Barbara Gordon being paralyzed was one of the few unchangeable “facts” of the DC Universe. Other heroes died and rose from the dead, recovered from various kinds of maulings and mutilations, turned evil and then redeemed themselves, but Barbara Gordon stayed in her wheelchair. Simone’s Batgirl #1 starts with the revelation that after miraculous cutting-edge surgery and a lot of physical therapy, Barbara can not only walk again, but she can also do all the kinds of superhero acrobatics that Batman-like characters are supposed to be able to do.

(Tangentially: the editors at DC have been reversing and undermining most of the contributions Alan Moore made to their superhero comics, seemingly out of spite that he’s tried to stand up for his rights as a creator with regard to his popular Watchmen comics).

As I mentioned up top, what I like about Simone’s work is that it reminds me of the comics I liked best as a 12 year old: superhero comics that were serious without necessarily being “grim and gritty”. They were more like soap operas with the occasional after school special thrown in, and, as opposed to the “deconstructionist” comics like The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen, they kept the colorful design and circuslike atmosphere of the traditional superhero book.

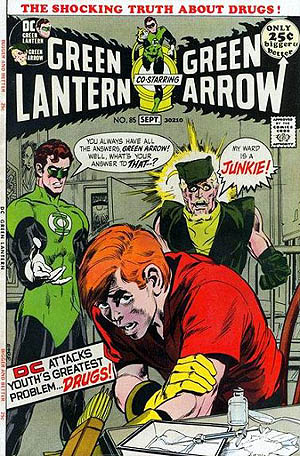

The granddaddy of these kinds of comics is the Green Lantern/Green Arrow series by Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams:

My favorite of the genre, though, was Marv Wolfman and George Perez’s New Teen Titans. I liked it better than Chris Claremont’s more renowned and equally soap operatic X-Men comics:

Simone does a pretty good imitation of these comics, which were almost cutting edge (for superhero comics at least) back in 1984. The big storyline in these Batgirl comics deal with Barbara’s concerns over whether or not she is mentally and emotionally ready to be a superhero again. She’s worried that the attack by the Joker has left permanent psychological scars that will prevent her from operating at her best.

Simone also abides by one of the central conventions of these comics: the villains must all be Thematically Appropriate. So, in these comics, the two bad guys Batgirl goes up against are both victims of trauma (just like she was), who are acting out in a socially destructive way. Sure, she has to stop them from committing crimes, but the big question is whether or not she can help heal them? Because, of course, if they can be healed, so can she.

One might be tempted to put this emphasis on trauma and therapy down to Simone’s being a woman, but that’s probably a mistake. You get the same themes and plots from the men who write these kinds of superhero comics, too: they’re all over Marv Wolfman’s Teen Titans series and Chris Claremont played around with the same kind of ideas in his X-Men stories.

Though I still find something about this approach appealing, I think Simone’s Batgirl comics fall a little short. For this kind of thing to work, you really have to embrace the symbolism and the fantasy. Using super villains as a metaphor for trauma only works if those super villains are larger than life: they must have mythic, supernatural proportions, like the spooks in a Stephen King novel or the bad guys in Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer show. Simone’s villains are too small scale, too human: they’re “more realistic” in ways that work against her story, because real people may respond to trauma by doing awful things but, for the most part, they don’t respond to trauma by launching nefarious, but metaphorically appropriate, super villain plans.

I have a hard time telling if there’s any speficic “woman’s perspective” that Simone brings to the superhero genre or not. Certainly, she must have some kind of insight into women that the average nerdy-comic-book-writing-dude doesn’t have, but the main difference between her comics and something like Red Hood and the Outlaws is that Simone’s aren’t as overtly sexist. I suspect she gets hired to write comics with female protagonists because she’s a woman, but I think that’s more about the editors at DC comics being pretty unimaginative.

“Annnnnnnd of course he can’t.”

“Okay. I admit it. As a plan, this kind of blows.”

It’s ironic snarkypants Batgirl! New and improved!

LikeLike

“Remind me to write about why I hate these contemporary superhero comic book covers…”

Is it because there’s too many objects cluttering the frame, the colors are all desaturated, and the heroine looks like a fierce trans-sexual?

LikeLike

Mainly because it doesn’t give any clue to what the story actually is (compare the top image with the Green Lantern and Teen Titans covers farther down the page).

But those are good reasons to hate them, too…

LikeLike

I had a feeling you were gonna talk about the abstract background. It might make for a fine poster, but yeah, not good for a cover. Generic.

LikeLike

Divorcing it from any action or narrative also makes the portrait approach fall flat. Portrait subjects must show subtle and suggestive expressions. Or if they’re dictators, they can strike bombastic poses. But when it’s an ordinary person, even if they’re a hero, an exaggerated pose without any motivation makes them look goofy, more pompous in fact than Henry VIII.

A narrative illustration with some action going on is not only effective as advertising for the inside, but is better at grabbing your interest. It sets up the composition of figures, ground, and movement. I browsed through some covers from the ’70s and ’80s, and the compositions look more striking than in any form of visual culture we have today. The colors and lighting were also more contrasting and fun to look at.

I realize this sounds like Art 101 stuff, but if it so regularly goes out of fashion, it can’t be. It’s more like “Art for Fun-Lovers 101” or something.

LikeLike

Exactly. Looks like I won’t have to write that post, after all.

LikeLike