Fenster writes:

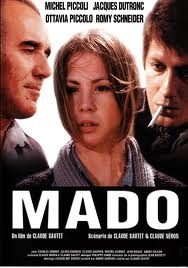

You can forget a lot about a film in 35+ years, and I forgot a good deal about Claude Sautet’s Mado, which I saw when it came out in 1976 and only saw again recently.

In fact, I had forgotten most of the plot and even the title, which made it hard to track down when I wanted to see it again from time to time over the years. I remembered a nuanced performance by Michel Piccoli and that the plot revolved around real estate development, the details of which were provided in luxurious detail unusual in film. That was striking.

I lost track of it until IMDB made it easier to identify films. The increased availability of otherwise obscure offerings brought it to my DVD player last week, where I was able to compare notes with my selective and shoddy memory.

The two aspects of the film that I recalled vividly remained striking. Piccoli’s performance is nuanced, and really interesting. And the film portrays aspects of business, finance and real estate development in a lot more detail than is normally the case, where they are typically treated superficially and as the occasion for hot action of one sort or another. Here, the details are afforded real respect.

But real estate development? 1976? Oddly, I suspect I was especially fascinated by that world in 1976. As I wrote at 2Blowhards some time ago:

Generationally speaking, while my dad’s formative years were molded by depression and war, mine were molded by two bookends separated by less than a decade: the cultural shifts of the late 1960s (made manifest most clearly by Woodstock) and the return-to-reality shocks of the mid-1970s. The latter was made manifest in my life via a series of awakenings that reminded me that, irrespective of many deeply satisfying Aquarian yearnings, the world-as-it-is is also important. And that world consists of many seemingly prosaic things, like municipal water systems and debt burdens. Thus it was that I was greatly influenced by everything from Polanski’s Chinatown to Caro’s The Power Broker in an end-of-an-era kind of way.

Mado was, I think, a similar slap in the face–a preview, if you will, of what adult life, and my life, might shape up to be like. Indeed, while I was never a real estate developer I did spend a number of years doing bond financings, so the preview element of the film was for me quite real.

And there are aspects to the film that mirror my 1976 perspective, and touch directly on the issue of young/old, business/pleasure, work/play and conventional/unconventional.

So with that, here’s the plot, including spoilers.

Léotard (Piccoli) is the head of a real estate development firm competing to do business on large projects in the Paris area. He is separated from his struggling and substance abusing wife and has taken up with a beautiful young woman named Mado (Ottavia Piccolo) , whom he pays for sex and companionship.

I don’t call Mado a prostitute since she would bridle at the term and I would like to stay on her good side. Rather, she’s something between a prostitute and a sixties/seventies free spirit, doing what she feels OK about doing.

Léotard is smitten and would like nothing better than to wean Mado of her other paying customers, some of whom don’t even pay, with the result that he is suspicious that she may actually be more attached to other men than she is to him, and it is starting to drive him quietly crazy.

Mado and Léotard are at the centers of two interrelated groups: a team of older, male real estate types working with Léotard and a group of younger men and women in their twenties who give off faintly countercultural vibes. The latter group doesn’t seem too concerned about work, though the old crowd and young crowd often inexplicably hang out together.

Now, the French they did anarchist and they did situationist, but they never really did hippie, so it would be unfair to call the youngsters that. But they have those tendencies in French form, and are even making a move to “get back to the land”, setting up an unresolved and unremarked-upon tension with their elders over respect for the land.

Léotard finds that the financial misdealings of a business associate have put his firm in serious jeopardy. The trail leads to another big developer, Lépidon, whose success as a developer comes from his corrupt political connections. Lépidon’s intention was to bring financial ruin for his own gain, and he appears to have succeeded.

Léotard hatches a scheme involving Mado. With Mado’s help, Léotard enlists the help of Manecca, of one of her “real” lovers. Manecca is another shady developer, but he’s got the goods on a politician tied to Lépidon. Léotard, who is jealous of Manecca and fancies himself a cut above, nonetheless uses his information to blackmail the politician in cahoots with Lépidon, in the process securing the rights to Lépidon’s project for a pittance. Lépidon is angry.

In the last act, the film looks to resolve several tensions: Mado and Léotard (love), Lépidor and Léotard (war) and the old/young thing (culture).

The young/old dichotomy resolves itself, after a fashion, when both groups pile into three small French cars, six to a car, and visit the countryside, where the development is to be located and also where the young crowd has acquired a farm that it intends to bring back.

So here we have two different responses by the urban crowd to the thinning out of the pastoral countryside: build or bring back. Interestingly, Sautet seems not to take a position, and is happy letting his ragtag group of eighteen drive around, Keystone Kops style, in three small cars investigating the countryside’s potential for redevelopment and/or renewal.

Indeed, this strange voyage provides the backdrop for the last act of the film, and for the resolutions of the other tensions. It is an oddly compelling ending.

We see Lépidor realizing that he’s been had, and sending his tough henchmen out to do damage to someone. At the same time we are tracing the voyage of the eighteen through the countryside, like the crowd of mimes in Blow Up. They drive through a punishing rainstorm and crash a lively party at a village tavern. They leave the party half-drunk with the rain coming down and quickly get lost. After several wrong terms in the rain and the dark they eventually all get stuck in deep mud in (wouldn’t you know) a construction site. The mood is still light but you begin to feel its potential to quickly turn dark, ominous.

Movie conventions are weighty things, and so you are primed as a viewer at this point to start dreading . . . the bad guy’s henchmen on the prowl, the gang of eighteen stuck in the mud, in the middle of a construction site, in a blinding rainstorm at night. It’s all very Hitchcockian, and you can’t help but think the plot will bring violence to Léotard’s happy crowd.

But no. Lépidor’s henchmen do away with Manecca, reasoning that he was the leak, and appear to leave it at that. Meanwhile, back at the construction site, the crowd is making lemons of lemonade. It’s nostalgie de la boue all the way, with the older real estate crowd and the young hipsters reveling in the rain and the mud, in the kind of Bacchanal you might expect from the erotic but still ever-composed French.

Morning comes as well as a tractor to save the day, and the celebrants begin to dry out in both senses of the term. But the news also arrives of Manecca’s death. Mado, already in emotional retreat from Léotard, retreats further. But this time, and for now, Léotard seems to let go his obsession.

So the film resolves itself relative to its business side via Léotard’s tainted victory. And the personal drama is resolved as Léotard finally lets go of Mado, returning to his wife and helping her to seek treatment.

There is a lot going on in the movie, a fair amount of which is under the surface. The unusual business detail underscores the factual, the prosaic, the no-nonsense. But that sits in nice contrast with the affairs of the heart and of culture that the film explores.

It’s a fascinating movie. There’s a thriller hiding in there somewhere. A love story too. But they’re so far back in the mix that, after an hour or so, you stop expecting them to pay off in anything resembling a traditional-movie way. What the movie ends up giving you is a bunch of sketches of moods, emotions, and people at various stages of their lives, and all of them bouncing off one another in interesting, pleasing ways. I guess the measure of its success is that so many of these sketches are recognizable and affecting. (The young people are like Alain Tanner’s idealistic fringe dwellers.) If there’s a flaw I think it’s in the conception of Mado, who’s a touch too angelic. (What was it that caused French directors of that era to latch onto the hooker as a symbol of purity? Mado and Karina in “My Life to Live” seem intended as more than just hookers with hearts of gold; they’re metaphorical somethingorothers.) But that’s made up for by the richness of the Piccoli stuff. What a marvelous performance, and Sautet really seems to empathize with the character. I, too, love that party scene. I love party scenes in general. I should do a blog post on party scenes.

LikeLike

Mado looked angelic, and meant no one no harm, and did what she wanted to why not? . . . but she remained for me somewhat ambiguous, in the vein of Freud’s comment about Lord what do women want?

The me decade of the 70s reflected the flowering (or rotting, depending on your POV) of the hyper-individualism presaged in the 60s by things like Hendrix’s “fall mountain, just don’t fall on me”. And so yeah in that era the free spirited gal who takes life as it comes, so to speak, was a real type, and often a positive one. I feel though that while Sautet (born 1924) may have been critical of Piccoli’s character, he still wants to tell the story through his eyes. I think to Piccoli (and maybe to Sautet) Mado isn’t so much angelic as inscrutable.

LikeLike

Pingback: Notes on “A Late Quartet” | Uncouth Reflections