Blowhard, Esq. writes:

I semi-enjoyed this newish Teaching Company series on the history of the medieval Crusades. I hesitate to fully endorse it because, while I think Daileader’s 3-part, 72-episode series on the Middle Ages (all of which are on sale now) is one of the best things I’ve ever heard, this series had too much detail for me.

The first 17 lectures are a narrative history of the eight major Crusades plus digressions into some of the minor Crusades. It’s interesting stuff, but there are so many characters, institutions, actors, and shifting alliances that I found it a wee bit hard to keep up. I quickly tuned out much of the facts and tried to focus on the broad outlines.

The last 7 lectures, though, eschew the who-what-where sequence of events and instead look at the social impact of the Crusades, while the last 2 lectures assess their long-term impact on history. Ultra-brief distillation: the Crusades, which lasted from 1098 to 1291, began when the pope issued a call for Catholic Europeans to come to the aid of Byzantine Christians who were being overrun by Muslim Turks in the East. Christian Europe also decided it was time to take back Jerusalem. Over the decades and centuries, the goals and reasons for the Crusades changed. Eventually, there would be Crusades against the Byzantines themselves, Crusades against heretics in Europe, and even Crusades against European Christians who had fallen out of favor with the pope.

Why were the Crusades so popular and long-lived? Many factors of course, but a major reason was that all Crusaders were entitled to a plenary indulgence. The plenary indulgence entitled the bearer to the remission of all punishment in purgatory for their sins. Who wants to be stuck in a celestial way station for tens of thousands of years waiting for their souls to be purified? The plenary indulgence erased all your penance, thereby ensuring that upon your death you’d go right to God’s side.

One of the ways the Crusades changed history was by leading to the Protestant Reformation. This is one of the great ironies of Western history: a campaign intended to unify Christianity by healing the rift between Western Catholics and Eastern Byzantines actually resulted in Christendom being further fractured.

You’ll recall that one of Martin Luther’s major beefs with the Catholic Church was over the issue of indulgences. At the beginning of the Crusades, plenary indulgences were only available to Crusaders, but over the centuries, “indulgence inflation” occurred until it got to the point that the Church was basically selling tickets to heaven. Some of this indulgence inflation was humanely motivated. For example, if Crusading knights were leaving their wives and children for years at a time, why shouldn’t the wife be given an indulgence too for all the sacrifices she had to endure? Conversely, some of indulgence inflation was basically a cash grab. Remember Chaucer’s scathing portrait of the Pardoner in The Canterbury Tales?

The sale of indulgences shown in A Question to a Mintmaker, woodcut by Jörg Breu the Elder of Augsburg, circa 1530.

In discussing indulgence inflation, Daileader notes:

Too much money came from indulgences and too many livelihoods depended on the indulgence market. The livelihoods of those who granted indulgences, those who served at pilgrimage sites to which indulgences came to be attached, those who bought the right to distribute indulgences on behalf of those who granted them expecting to get a profit and return on their investment; the preachers, the pardoners, the local officials and rulers who demanded a cut of the take in return for allowing the indulgences to be distributed in their territories; parish priests who demanded a cut in return for allowing pardoners to speak during mass; the list of those who were profiting from this went on and on and on.

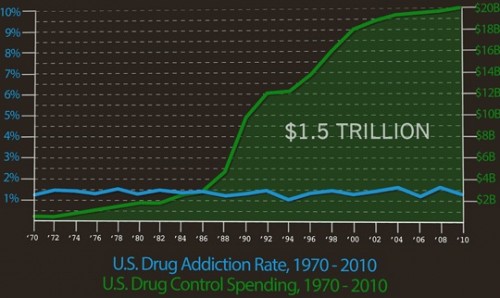

So we had a situation in which a massive centralized project, which has likely outlived any usefulness it may have had while resulting in diminishing returns, creates an economy upon which legions of people are dependent. I couldn’t help but think of this:

How many politicians, government bureaucrats, police, lawyers, judges, prison contractors, prison guards, unions, mental health professionals, experts, and other consultants continue to rely on the criminalization of drugs?

That drug-war chart is just amazing.

LikeLike

To change the topic slightly, the Manolo has this theory that the indulgences were the first standardized product of the age of mass consumption, and that the preacher Johannes Tetzel could therefore be considered the first great advertising executive.

LikeLike

Pingback: The War on Drugs as a Modern Crusade

Pingback: My Year in Books | Uncouth Reflections

Pingback: UR Explainer: Kaley v. United States | Uncouth Reflections

Pingback: Quote Du Jour: Bent Flyvbjerg on Megaprojects | Uncouth Reflections

Pingback: NYC Notes, Part 3: The Cloisters at Fort Tryon Park | Uncouth Reflections