The Mistaken writes:

Explaining Postmodernism is the clearest book I’ve read on postmodern theory and how it fits into our current political climate. Stephen Hicks is a professor of philosophy at Rockford University in Illinois, with a PhD in Philosophy from Indiana University. He is or has been affiliated with the Objectivist Center and is currently director of the Center for Ethics and Entrepreneurship at Rockford. He’s pro-business, pro-capitalism, and sympathetic to classical liberalism, the Enlightenment, and modernism.

More importantly, Hicks hates postmodernism. This makes him ideally suited to write a book trying to explain it. Almost every other book on the topic is written either by postmodernists in their typical, obfuscatory, jargon-laden, aren’t-we-clever style or by Marxists, who like some aspects of postmodernism but dislike a lot of it because it isn’t Marxist enough.

Hick’s main thesis is simple, as expressed in this meme:

The book is wide ranging. It starts from a description of where we are now and how generally insane postmodernism is, then turns to intellectual history with a discussion of the Counter-Enlightenment and its challenges to realist epistemology. It then discusses post-Enlightenment philosophers from Hegel to Nietzsche to Heidegger and how they built on this Counter-Enlightenment current.

This current is broad and has a number of variants which Hicks describes for a few chapters. He then detours a bit by discussing the overlap between what he calls collectivist right and collectivist left thinkers. He then gets back to his laser focus on leftist intellectual history, which he decimates. Finally he turns to the postmodernists themselves, and their immediate precedents, such as the Frankfurt School, and reduces it all to a smoldering pile of ashes. Intellectually, that is. Because like it or not, the postmodernists are winning, and Hicks knows it.

Though clearly written, his argument is complex, so I’ll take it point by point:

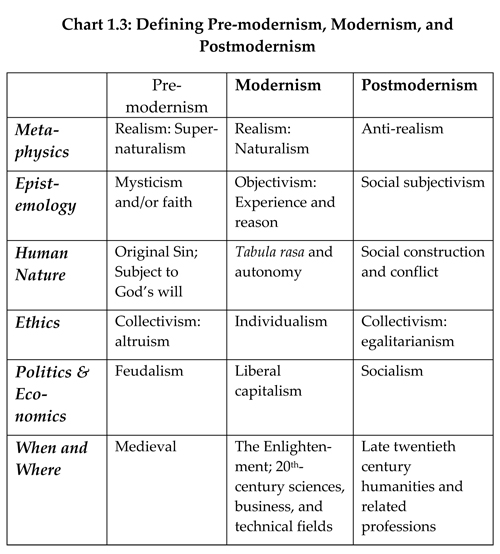

- We are in a postmodern age now, because postmodernism is the main intellectual movement of our time, replacing modernism.

- Postmodernism is opposed to universal truths and “universal necessities” including Reason, Truth, or Knowledge.

- Most postmodernists are expressly political – they “deconstruct reasons, truth, and reality because they believe that in the name of reason, truth, and reality Western civilization has wrought dominance, oppression, and destruction.” They want to “exercise power for the purpose of social change.” Males, whites, and the rich have more power and thus are targets.

- Metaphysically, postmodernism is anti-realist, stating that it is impossible to speak about an independently existing reality. (Of course they contradict this all the time by complaining about an independently existing reality of mean old white men who are probably all in the Klan, but I digress.)

- Epistemologically, reality is assumed to be socio-linguistically constructed. Reason doesn’t arrive at reality.

- Postmodernism is collectivist. Groups are more important than individuals. Individuals are collectively (socially) constructed based on the groups they are part of and these groups are often/usually in conflict.

- The ethics and politics of postmodernism side with groups perceived as oppressed, unless they are white, male, etc.

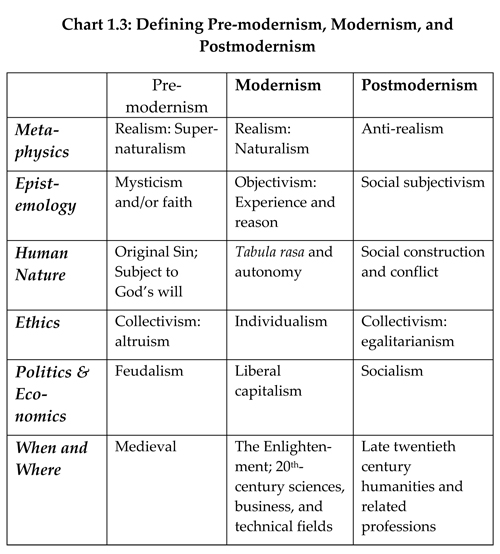

- Postmodernism’s essentials are the opposite of modernism (i.e. Enlightenment thought and science) and also differ from pre-modern positions.

- Postmodernism has its roots in the battle between the Enlightenment and the Counter-Enlightenment. This starts with Kant. Kant said that objectivity doesn’t work because empiricism goes through our senses and puts an obstacle between reality and reason – our internal representations and concepts. Of course we have senses. But Kant says the existence of senses and their identity means they are obstacles to direct consciousness of reality. So the blow to the Enlightenment came from two sources: Senses cut off reason from direct access to reality, and concepts seem irrelevant to reality or limited to contingent truths. Long story short – the “reality” we can study is merely in our brains. This is the Kantian position. Much of modern philosophy stems from this. (My apologies if I’ve oversimplified this part. Hicks writes an entire chapter about it, but I’m not a philosopher, and am fine with just dismissing Kant and moving on.)

- After Kant the Counter-Enlightenment continued with philosophical approaches such as structuralism – a linguistic version in which everything (and thus reality) is about language. Another Counter-Enlightenment stream would be phenomenology, in which we try to avoid assumptions and describe reality as objectively as possible or bracket our opinions to “get to the thing itself” as Husserl might say.

- There is a fairly long discussion of Hegel, which seemed somewhat unnecessary. Essentially Hicks describes Hegel as stating that the subject doesn’t respond to external reality, the whole of reality is created by the subject. Furthermore, for Hegel, there are always contradictions in reality, which makes truth relative to time and place. The collective, rather than the individual, is what is important.

- Then came Nietzsche and the irrationalists who agree with Kant that reason is unable to know reality, agree with Hegel that reality is conflicted/absurd, conclude that reason is trumped by claims based on feeling, instinct, or leaps of faith. The non-rational and irrational yield deep truths about reality.

- With Heidegger we reach metaphysical nihilism. Hicks says Heidegger prefigures postmodernism by integrating speculative metaphysical conjecture with irrational epistemological streams. For Heidegger, the entire Western tradition – whether Platonic, Aristotelian, Lockean, or Cartesian – is based on subject/objection distinction and non-contradiction and must be overcome.

- Getting back to the postmodernists, they later adopted much of Heidegger but removed the metaphysics and mysticism (the best part) from Heidegger’s philosophy. Postmodernists are anti-realist: they say it is meaningless to speak of truth. Postmodernists then compromise between Heidegger and Nietzsche by incorporating Heidegger’s epistemological rejection of reason while elevating Nietzsche’s power struggle over Heidegger’s metaphysical quest for Being.

- This leads finally to Hicks’s FIRST THESIS: Postmodernism is the end result of Kantian epistemology and its Counter-Enlightenment. Postmodernism is the first synthesis of these trends: metaphysical antirealism, epistemological subjectivity, feeling as the root value of all ethics, relativism, and devaluing of science. From this, postmodernists just follow their feelings, as pre-moderns followed their traditions (and religions). But postmodern feelings are primarily rage, power, guilt, lust, and dread.

- Because of the dominant importance of social constructionism, independent individuals are not in charge of these feelings. Identities are the result of group membership: racial, sexual, economic, ethnic. And all will be in conflict.

- There is an enormous problem, which leads to Hicks’s SECOND THESIS: Postmodernism can’t only be about epistemology and anti-realism, because postmodernists are always Leftists. Also postmodern rhetoric is very harsh, melds with political correctness, and currently is best exemplified by the non-stop effort to call everyone they don’t like a “racist”, “sexist”, “bigot”, “white nationalist”, and eventually “Nazi.” The final argument is basically just ad hominem. Why?

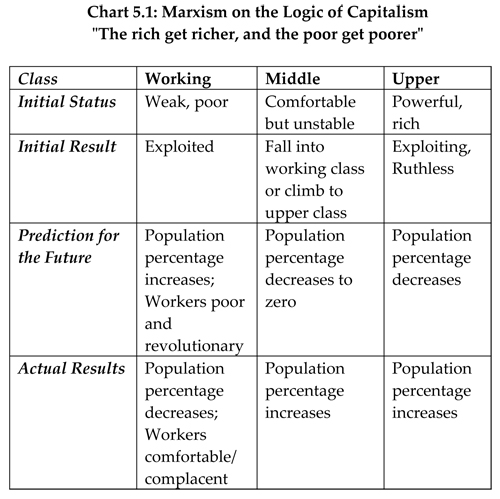

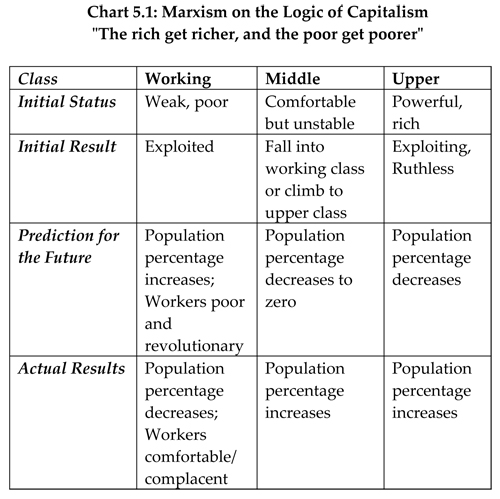

- Hicks’s explanation is this: Marxism was initially modernist and made four main testable scientific claims about how capitalism would collapse and be replaced with communism. Each was eventually refuted. In real countries with real economies, classical liberalism (or some variant of it) won. This chart shows the Marxist predictions v. the actual results.

- Hicks states that the empirical evidence is strongly against socialism working anywhere with any kind of good long-term results. Capitalism led to better living conditions while no socialist experiment has worked, and most or all have been totalitarian and include widespread slaughter of their own population, as depicted in this chart.

- This leads to Hicks’s MAJOR HYPOTHESIS: “Postmodernism is the academic far left’s epistemological strategy for responding to the crisis caused by the failures of socialism in theory and practice.” Basically, the Left wanted socialism to work. It didn’t. Because of that they abandoned facts and went with feelings. Sound familiar?

- Hicks goes on a long tangent against collectivism in all of its forms, which he traces to Rousseau, then to left and right branches. The right branch is primarily German and goes through Herder eventually into National Socialism. This part of the book was interesting in making explicit links between socialism and Nazism, and people who like to argue about whether Nazism is leftist or rightist should read it, but I found it mainly irrelevant to the major theses of the book. I think it is clear that Hicks is not a fan of nationalism. But if you are, don’t let that deter you since his absolutely savage attack on the Left is worth reading no matter what.

- Hicks demolishes socialism in Chapter 5 which is, quite frankly, fantastic. Marxism’s main two arguments were: 1) Economically, capitalism would eventually fall apart because socialism was more efficient. It turns out it wasn’t and Hicks presents a bit of data to prove it. 2) Morally, capitalism is evil and socialism is good. Marxists thought capitalism would collapse because of exploitation and oppression of workers would lead to revolution. But it didn’t. Because capitalism isn’t inherently evil, and socialism isn’t inherently good. Duh.

- By the 1950s, Lenin’s theory of imperialism – that the misery of capitalism and oppression would essentially be off-shored to the Third World, one of the more reasonable parts of Marxist theory in my view – also started looking wrong. Third World countries that had adopted capitalism earliest seemed to be doing better than those that hadn’t.

- By 1956, socialism only had the moral case left because the economic case has been destroyed by facts. Then the USSR crushed the Hungarian revolution and Stalin’s crimes were exposed. Now, much of the moral case was destroyed too.

- In reaction, communists and socialists then put their faith in Mao, but soon his crimes surfaced as well.

- So the Left was in a profound crisis.

- Since the Left had now utterly failed in practice everywhere, they tried anew. Their new strategies split them into camps and changed some basic underlying Marxist assumptions in four ways: First, they shifted from a focus on need to a focus on equality. The original idea had been not to leave people in dire need. Now it was to “make everyone equal.” For instance, the socialist German government began splitting large businesses up to make them “more equal” in size. Also, rather than focusing on absolute poverty, Leftists began focusing on relative poverty, i.e. making sure rich people didn’t get too rich. Second, the growth of identity politics. Instead of focusing on “the poor” or working class, focus shifted to minorities, women, homosexuals, etc. Again, Leftists refocused not on absolute conditions, but relative conditions. This is still all about equality, i.e. gay marriage is based on a relative equalization of conditions, rather than an absolute need. Third, a change in ethos from “wealth is good” to “wealth is bad” and concomitant focus on how consumerism is making the proletariat non-revolutionary. This stems mainly from Marcuse and the Frankfurt School. Fourth, radical left environmentalism. From this viewpoint capitalism has both oppressed nature and alienated man from nature. The solution is radical egalitarianism between species, best expressed in philosophies like Deep Ecology and animal rights.

- Hicks states that this all happened because the Left started with the concept of a universal proletarian which is an idea based on reason, so when they gave up on reason they gave up on this concept. Also, Leftists, increasingly academics, realized that the masses aren’t smart enough to understand these abstractions and generalizations, but they can understand identity politics, because any simpleton can. “My group is oppressed by the majority!” doesn’t require any further analysis or intellectual heft, thus its ubiquity today.

- Also Maoism’s influence became more important: Revolution anywhere, by anyone, by any means.

- Hicks focuses on the role of Marcuse and the Frankfurt School. They added psychology, especially Freudianism, to Marxism, to justify the psychological basis for the lack of the predicted but not-ever-happening proletarian revolution. Then they tied Freudian notions of repression to capitalism.

- This repression may create its own destruction by bursting out in violence, the marginalized revolting, and criminality. Marcuse said they should look to the marginalized to fight back. This ring any bells for anyone recently?

- The blend of “The marginalized are our hope” and “Violence is OK” led to a strong turn towards irrationality and violence among leftists in the 1970s.

- To recap, at this point in Leftist intellectual thought: 1) Reason is out, passion is in; 2) Away from theorizing, decisive action now; 3) Moral disappointment in socialism, rage at the failure and betrayal of the utopian dream; 4) Psychological blow of seeing capitalism winning and smirking; and 5) Political justification of violence in theories of Frankfurt School.

- This led to the explosion of Leftist terrorism of the 1970s, but that was easily crushed by the capitalist state. Yet another Leftist failure. See the chart below.

- At this point we have the total collapse of the New Left. But, largely undeterred, Marcuse shrugged and said the Left will go to the universities and regroup. This then became postmodernism. Hicks focuses primarily on four of its main representatives: Foucault, Derrida, Lyotard, and Rorty.

- These and other postmodernists were best suited to carry on the fight from the Left. Because they were academics, their main weapon was words. (And they don’t hesitate to overwhelm the reader with them. Ever try to actually read Derrida?). And because their epistemology held that words aren’t about reality, words must be a rhetorical weapon. Here Hicks presents the best chart in the book, a flow chart of failed Leftist strategies over the years that stands on its own as a minor masterpiece.

- In the final chapter Hicks is able to answer his first question: Why has a leading segment of the Left embraced skeptical and relativist epistemological positions? Well, because for a modernist, words link to real-world meanings. But for a postmodernist, words link only to other words because we cannot get outside language. Therefore, words can just be used rhetorically, as a weapon. There’s no need to correlate one’s words with anything like “reality”, since “reality” doesn’t exist and is just a socio-linguistic construction. Meanwhile, there are conflicts raging between groups, and given postmodern ethics, that’s really all that matters, so words should be used as weapons. This explains the harsh rhetoric, ad hominem, straw men, always trying to silence people whom you disagree with by saying they are using “violence” by speaking, and the rest of the bullshit that has affected public debate about almost anything.

- See, if you’re a postmodernist, you don’t worry about truth. You worry about emotions and winning.

- Postmodernism, says Hicks, is like the religious challenge to the Enlightenment. Adopt an epistemology that tells you that facts and reason doesn’t matter. “Feelings and passions are better guides.” And because you believe in the importance and inescapability of contradiction, use contradictory discourse as a political strategy.

- Hicks gives some examples: postmodernism is relativist, but it is at the same time is correct; all cultures are equal of respect except Western culture which is uniquely bad; values are subjective but racism and sexism are extremely terrible.

- OK, still with me? At this point Hicks concludes his polemic by stating that there are three possible reasons why postmodernism has these contradictions between its absolute and relativist positions: Reason 1) Relativism is primary and absolutism is secondary. But this can’t be true because they largely all agree on absolutes (politics). So forget this reason. Reason 2) The absolutes (politics) are primary, so the relativism is a rhetorical strategy to push those positions. Reason 3) Postmodernism is ultimately contradictory but postmodernists don’t care because they are essentially anti-social, destructive nihilists. (Sort of James Burnham’s position in his masterful Suicide of the West).

- Because R1 is ruled out, R2 or R3 must be true. Both are Machiavellian positions.

- With postmodernism, you can always divert from arguing about facts into arguments about epistemology. So if the facts don’t support you, for instance, just say there is no truth and your opponent is arguing from a position of privilege.

- Or, rather than reading the Western canon in a way that explains and justifies capitalism, individualism and liberalism, you can just say those books were written by white men and nobody should be forced to read them. That way rather than having to actually debate and disprove ideas, you can just dismiss them.

- This ends in nihilism. Postmodernists attack the Enlightenment on moral grounds, without moral grounds, or without referring to real facts or arguments. In this way you can undermine people’s confidence in science, technology, our economic system, social relations, individualism, themselves, etc.

- Fin.

Some concluding remarks. These are my opinions, not Hicks’s:

In the last 20-30 years, academic postmodernism indoctrinated an enormous number of people who now hold influential positions in the media, entertainment, and tech companies. It infected law schools and the social sciences, resulting in numerous people in government also holding these positions, whether in the US or Western Europe.

The speed with which postmodern ideas have become “common sense,” particularly to cultural and media elites, the professoriate, and urban young people is breathtaking. Social media companies and the new Internet media, largely run by people subjected to postmodernist indoctrination in the universities play an enormous role here. Whatever the reason, in the last 25 years postmodernism has gone from a minor academic oddity to the fundamental thought matrix of our age.

Most of our contemporary popular debates about race, sexuality, etc. are based on the tactics and nihilistic philosophy of postmodernism. Unable to address conventional Marxist or Leftist politics, they have turned to the cultural and social sphere. But they also have invaded legal and policy spheres and are, essentially, on a mission to destroy the West and its traditions. This is indeed nihilism. But it is targeted nihilism – focused on its enemy. And while Hicks thinks the target is modernism, it also includes anything left of pre-modernism or tradition. It includes not just the individual, but the family. Not just rich people, but the middle class. Not just white elites, but white proletarians. Not just parts of the West, but the entire thing.

To save the West and its traditions, whether pre-modern or modern, postmodernism is going to have to be stopped. It is the dangerous ideology fundamentally underlying all of the lunacy and insanity we see on a daily basis today.

Hicks does a masterful job showing us how, and why this has happened. While I disagree with his dismissal of pre-modern tradition and his statements that the collectivist right is dead and gone, his main points are solid and on target. (To be fair the book is a few years old, before the most recent collectivist right resurgence.)

This is an important, vital book for our time. Particularly if you have children of or near college age, it is important that they read this to counter the postmodern brainwashing that passes for education in our institutions of higher education and increasingly even elementary and secondary schools.

Postmodernism is the worst thing the Left has come up with since the fall of the major communist states. Its enemies are logic, realism, and calm, rational, empirically-based argument. It can and will be defeated. To go back to Hick’s chart, it must end, as all other Leftist attempts prior have ended, as failures.

Related