Fabrizio del Wrongo writes:

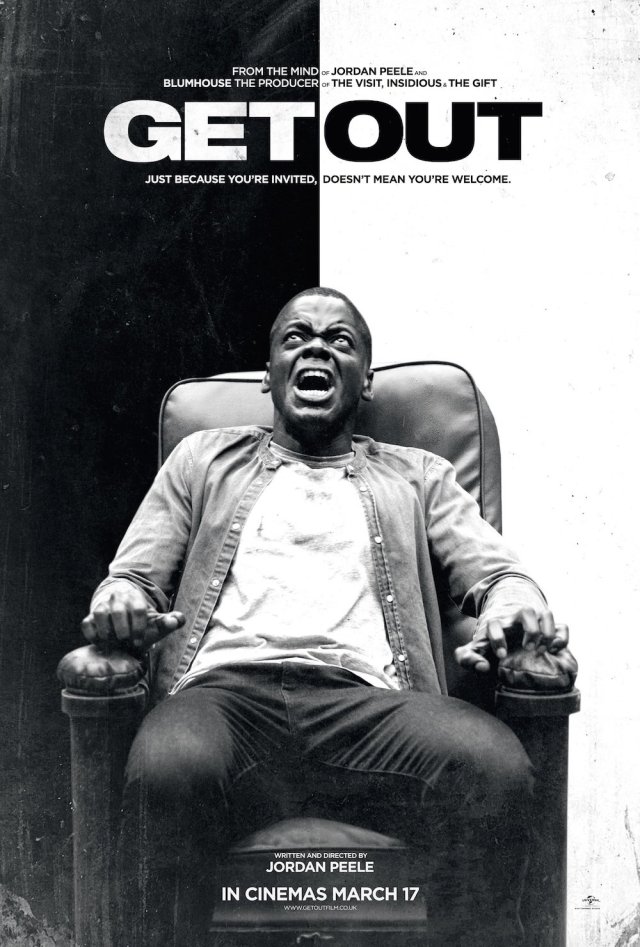

Though Jordan Peele’s “Get Out” is set among the suburban white elite of Everywhere USA, its concerns are firmly rooted in the plantation. It ascribes to white liberals the motivations of slave-holders, and then asks them — its principal audience — to cheer their own annihilation. As a satire the movie is curiously unpointed; it rarely connects with observable reality. The servile blacks who toil obediently in Massa Whitey’s geranium beds seem like figures of the 1950s rather than the 2010s. Either Peele is pretending that it’s still common for blacks to hold this type of position, or he doesn’t realize that Guatemalans exist, and that they’re cheaper and complain less. The picture I take to be Peele’s model, “The Stepford Wives,” was at least timely. Peele, by contrast, is skewering attitudes that were expunged by his subjects 70 or more years ago (if they ever held them at all). Perhaps he’s not skewering these attitudes so much as trying desperately to prop them up, to keep them alive in our imaginations? Their rhetorical value is obvious even when their satirical value isn’t.

The movie might have worked had Peele brought us inside the mentality of the black man who yearns for white acceptance, and then used that yearning to generate, and comment on, racial anxiety — the kind of anxiety one senses in Barack Obama when he tries to appeal to urban audiences. But for it to operate in that manner we’d have to understand hero Chris Washington’s attraction to his exploiters, to feel his desire to win favor with white society. Peele doesn’t bother with any of that: His suburban whiteopia is nearly as creepy and menacing as the Overlook Hotel in Kubrick’s “The Shining”; whatever it is that’s happening there, we want no part of it. Since it’s obvious from the start that the family has done something awful to its black servants, there’s no thrill in Chris’ slow realization of the underlying horror, and this forces Peele to fall back on schlocky gross-out effects to fulfill the requirements of the genre. Meanwhile, Chris looks uncomfortable and makes panicked phone calls, and the movie develops into a grim and rather inert affair involving a patriarch who, like a Bizarro World Yakub, surgically creates zombie blacks to trim his hedges. The narrative drive of “Get Out” becomes inseparable from its inevitability: There isn’t much to do but wait for the virtuous bloodletting. I’ve previously expressed my distaste for the ideological revenge picture. Is it a feeling of righteousness that people get out of these movies?

If the experience of watching “Get Out” feels a bit like sitting on a barstool and waiting to be punched in the face, it’s partly because Peele makes Chris a sacrificial victim on the altar of white villainy. The blaxploitation movies of the ‘70s were often explicitly anti-white, but we could appreciate them as black fantasies about putting the white man in his place, and their heroes were charismatic and larger than life. Chris has one interesting character trait: he smokes; and even that isn’t used in a way that’s interesting. (His having lost his mother as a boy is just another aspect of his virtuous put-uponness.) While his white girlfriend, Rose (a devilish Allison Williams), is vivid and opinionated, it’s never made clear what Chris thinks of race relations or interracial dating, and actor Daniel Kaluuya is content to fill him out with an anodyne, “it’s all cool, bro” passivity. It’s possible that this is part of Peele’s commentary, and that he intends Chris to embody the placidity and inoffensiveness that he imagines whites require of blacks who try to assimilate. But by making Chris so colorless, he resigns him to being a device. It’s odd to see a movie ostensibly derived from Ta-Nehisi Coates’ writings on racism treat its hero as a “black body,” but that’s largely what Chris ends up being: Like Camille Keaton’s rape victim in “I Spit On Your Grave,” he’s there to sustain abuse, and to justify the compensatory carnage. (Don’t get your hopes up, exploitation fans: “Get Out” has little of the nervy visceralness of “Grave.”)

It’s also possible that Peele disapproves of Chris, and that he’s punishing him for being an Uncle Tom. This would explain why Peele seems more interested in Chris’ friend, Rod. An airport security agent, Rod is played by the wonderful LilRel Howery, who gives the character a warmth and an energy sorely lacking in the rest of the picture. Also, Rod provides “Get Out” with one of its few flashes of observational sharpness: Blacks dominate the staff of some major airports, and it’s funny that it’s the airport guy, and not the hated police, who rides to Chris’ rescue. (Another funny moment: Rose listening to “Time of My Life,” from “Dirty Dancing,” while idly browsing photos of half-naked black men and munching Froot Loops.) I suspect Peele’s sympathies lie with the suspicious, race-conscious Rod, and that the drab, conciliatory Chris is intended as a warning to blacks against the dangers of allowing white people to use them as a “black bodies.” But if that’s the case, what Peele is offering is little more than a demonstration of theorized victimhood — one unlikely to impress the viewer who thinks Ta-Nehisi Coates is full of shit.

Reduced to the basic message of its title, “Get Out” suggest that blacks are best if they avoid whites and stay out of the suburbs. This raises the question: Has Peele made a pro-segregation movie? If I felt that was his intent, I might appreciate “Get Out” as a work that, at the very least, attempted to take the piss out of contemporary social protocol. But I think “Get Out” is better understood as something much more conservative: As an expression of a symbiotic relationship between blacks whose claims of exploitation give them political power, and whites whose feelings of racial guilt found their morality. If the allusion to this peculiar nexus, the basis of so much in contemporary politics, doesn’t constitute a message on the part of Peele, it’s the fulcrum on which his movie pivots, and I take it to be the key to understanding the overheated response from white critics who have fallen all over themselves in praising a work that condemns them for feelings they’ve likely never experienced. If a major critic’s recent apology for daring to find sexual interest in “Wonder Woman” didn’t convince you that masochism is a prime driver of contemporary cultural discourse, perhaps the RottenTomatoes score of “Get Out” will: Only two mainstream critics failed to praise it, and one of them — Armond White — is black.

I devote so much space to the movie’s messaging because if one isn’t dwelling on what Peele is trying to say in “Get Out,” there’s not much to train your intellect on while watching it. (Stylistically, it’s as flatly meretricious as an number of indie films made be any number of white people.) All things considered, my hunch is that Peele is simply grasping at the straws of political convenience, and that he hasn’t bothered to vet his gripes for internal logic or consistency. At times he seems to be working at cross-purposes. For example: He both ascribes to whites a desire to use blacks for sex, and condemns the stereotype of black potency. It’s as though he hasn’t realized that, if the stereotypes were baseless, there would be little point in acting on them. Perhaps the movie is most enjoyable when used as a springboard for examinations of this and similar glitches in the ideological matrix. My favorite such glitch: “Get Out,” beloved of progressives across the land, is the most popular anti-miscegenation film since “The Birth of a Nation.”

Digging down into the logic and consistency of this movie might be putting it under too much stress. I get the feeling of a satire taking swings rather than a stringent exploration of race.

I think the most interesting, and amusing, takeaway is that … blacks really don’t like the Democrat liberal white much either. Insincere and untrustworthy.

http://verysmartbrothas.com/get-out-takes-cultural-appropriation-to-the-cultural-harvest-level/

http://verysmartbrothas.com/10-pitch-perfect-examples-of-yeah-thats-some-white-people-shit-in-jordan-peeles-get-out/

http://verysmartbrothas.com/what-becky-gotta-do-to-get-murked-white-womanhood-in-jordan-peeles-get-out/

(Scan through the comments too.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think it’s true that satires often aren’t logical or consistent. I enjoyed Spike Lee’s brash and sexy CHIRAQ, and I wouldn’t accuse it of being logical. But in the case of GET OUT, I don’t think there’s much to appreciate outside of the message. And so you’re forced to examine it. Also, CHIRAQ wasn’t hailed as the work of a genius who has finally revealed the secret racial hang-ups of white people.

LikeLike

Second Glengarry’s comment. Meanwhile…

For example: He both ascribes to whites a desire to use blacks for sex, and condemns the stereotype of black potency. It’s as though he hasn’t realized that, if the stereotypes were baseless, there would be little point in acting on them.

I’m reading this as “whites stereotype blacks as sexually potent because there is a basis to assume blacks are sexually potent”. Perhaps Peale is saying “people shouldn’t be fetishized” and “stereotypes are insults to the individual”.

LikeLike

I don’t have an opinion on black potency. Peele makes a dig at whites for believing stereotypes about the sexiness of blacks. But he also makes the point — quite loudly — that whites are eager to sleep with blacks (and in doing so further exploit them). I’m sorry, but I find this somewhat inconsistent. What does Peele think of the issue? Is it okay for whites to find blacks sexy? He leaves it vague (which I think is a little shitty), so it comes across (at least to me) as him having his cake and eating it too. If I felt the movie was saying, “Sure, blacks are sexy as f**k, but you aren’t getting any, so don’t get your hopes up, whitey,” I might have found it ballsy and amusing. But there’s nothing brash or funny like that in this rather dreary collection of academic racial gripes. I think Glengarry’s suggestion is probably true, and Peele is simply swinging wildly in the hopes of landing as many blow as possible. How far that carries you towards an appreciation of the movie is necessarily a matter of taste.

As to your suggestion that Peele is making a simple point about the evil of stereotypes: I’m not sure I buy that in light of the fact that his movie is filled with white stereotypes. But, of course, this sort of politicized point scoring is rarely logical, so you may be onto something. I bet Peele’s response to this particular criticism would match yours pretty closely. Personally, I found the point-scoring aspect of the movie to be pretty unpleasant.

LikeLike

Related to point scoring, I thought this comment was pretty jaw dropping (from the third article above).

By an Associate Professor of Afro-Afro, no less. Crikey, I wouldn’t leave that one alone with white children.

LikeLike

A youtube review exists. Well… until youtube banned it. Get;Out: A Review for Non-Racists.

LikeLike

May I raise a point of style? I hate this cliche, “have your cake and eat it too”. If I have cake then I damn well expect to be eating it.

LikeLike

Do we really have to explain it?

LikeLike